“I can see it in your eyes. We can do this.”

I’ll always remember hearing those words from my personal racing manager, Mick as I lay in the hospital bed. I was a successful motorcycle racer and it had only been a matter of months since I’d led in the British Championships, aged just 18. Suddenly, I was 18 with ankylosing spondylitis and borderline osteoporosis.

Nobody in my family had arthritis and I didn’t know much about it, except what I’d been told. My bone density was that of an eight or nine-year-old, which was a shock – I was already about 40 years younger than the other patients on the ward! This was all quite intimidating for me at the time, bearing in mind I’d only gone in for a hip scan – we thought the pain was probably the result of a recent motocross crash. Two weeks later, I was still there, having hydrotherapy, physio and an infusion drug treatment.

When Mick visited, he looked me in the eyes to see if I was ever going to ride a motorbike again. To say at that moment that he still believed in me, I knew with him as my mentor and my family by my side, he was right. We were going to show everyone what we were made of.

The pain couldn’t be any worse

The support network I had looking after me during my diagnosis and racing career was amazing. I think without them, I potentially might have given up racing, but I didn’t contemplate it once. Instead, I changed the way I rode the bike by altering my body positioning to try and reduce risk. I tried to develop a style and an ability where I had a lot of feel, meaning I could avoid crashing. In my head, I wasn’t ever going to be in any more pain than I already was. I figured, I’m in pain anyway – I might as well continue racing!

In hindsight, it was probably naive to think the amount of pain I was in couldn’t be any worse. In reality, I couldn’t train as much as I wanted to because my body wouldn’t let me and that stressed me out. The arthritis held me back – I felt like I should probably stop doing certain things as I worried about making my illness worse, leading to more suffering.

Back on the bike

My first post-diagnosis ride was at a practice day – basically to see if I still could ride! It quickly woke me up to how hard it was going to be, but importantly, it gave me information to work from about what needed to be done next to improve.

Although I had medication, I was in agony and had stiff joints every day – some days worse than others. It took around four hours after waking up to get to an operational level, but even then I had to think carefully about what I did for the rest of that day. As riding a bike is very physical, you have to make small movements to make big impacts and be very fit to do it competitively. The issues with my arthritis prevented me from being as fit as I’d like, which meant I had to work extra hard – harder than most people – and that’s what I dedicated my days to.

Round 12

Round 12

As one of the younger up-and-coming riders at that time, things had just started taking off for me career-wise, but that was before my body took over. I had a British Championship ride already lined up and should have been getting more racing experience, but instead had to sit it out and wait until I was ready. I worried I’d missed my opportunity because I’d had a year off.

A new bike had been kept free and was waiting for me. I put a lot of work into getting onto that motorcycle – for physio, I was stacking shelves at Safeway and turning it into a race! I finally made it onto the track at that year’s final round.

Getting back on the bike, I wasn’t nervous but wondered if I could still race like I used to.

A shock to the system

It didn’t go well. I got smoked!

I had no clue what to expect – I hadn’t ridden the bike before or rode in that championship either, but as soon as people started passing me in the race, I felt like it shouldn’t be happening. I found it embarrassing. I went from winning races against some very talented people in the previous two years to getting hammered. I didn’t crash, but didn’t do very well which was a bit of a shock to the system! In the three years I’d been racing, I hadn’t ever been that bad. I didn’t like it and didn’t want to feel that way again.

The way I looked at it was that I hadn’t raced for a year. It was also a new bike with a lot more horsepower than anything I’d been on before. It was a lot harder to ride and faster than what I was used to! I saw it as a chance to regroup, to start again at the next British Championships and see what happens.

On the positive side, knowing I actually could race was amazing. It was a little overwhelming, after everything I’d been through. I realised I had this second chance and all of these people sticking by me – my personal manager, parents, sister, friends, the racing community – I wanted to make them proud. It was cool seeing people being happy for me and believing in my abilities.

Fuel for fire

I never considered giving up racing – it was frustrating when I didn’t perform as well as I could, but it wasn’t my time to stop.

I never considered giving up racing – it was frustrating when I didn’t perform as well as I could, but it wasn’t my time to stop.

I was determined to keep going. I had hope that one day I’d reach a point where I could really show everyone what I could do – a point when I didn’t have the pain holding me back.

I refused to give up. I wanted to prove something.

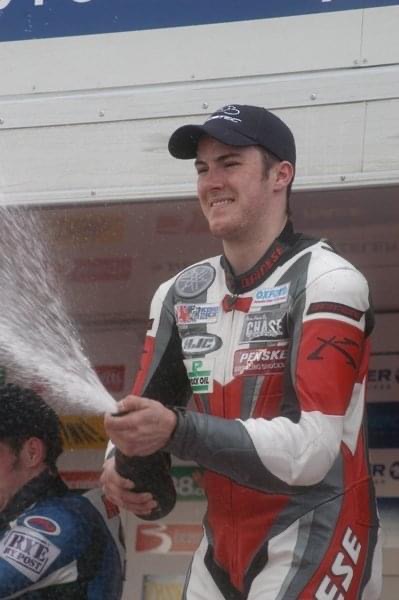

After being smoked in that last race, the following year I won the same championship with nine out of 12 race wins.

Using arthritis as fuel for fire, I won the Superstock Cup.

About Peter

A former British Championship motorcycle racer, Peter was diagnosed with ankylosing spondylitis aged 18. Despite being in constant pain and battling with the effects of arthritis every day, Peter pursued his passion and enjoyed huge success in the world of racing for several years. Now retired from professional motorcycling, Peter is benefiting from anti-TNF treatment. Originally from Staffordshire, Peter currently lives in Leicestershire where he continues to live his dream, by working in research and development for one of the world’s oldest and most iconic motorcycle brands, Triumph.